MANIFESTO OF CANADIAN DESIGN AKAFLDWRK

HEAVY ABUNDANCE

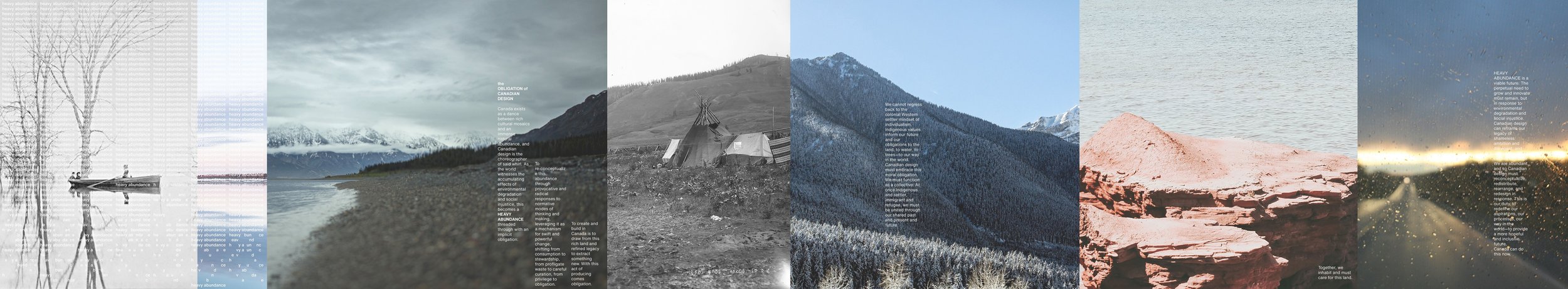

the OBLIGATION of CANADIAN DESIGN

Canada exists as a dance between rich cultural mosaics and an immense natural abundance, and Canadian design is the choreographer of said whirl. As the world witnesses the accumulating effects of environmental degradation and social injustice, this becomes a HEAVY ABUNDANCE threaded through with an implicit obligation:

To re-conceptualize this abundance through provocative and radical responses to normative modes of thinking and making, leveraging it as a mechanism for swift and powerful change, shifting from consumption to stewardship, from profligate waste to careful curation, from privilege to obligation.

To create and build in Canada is to draw from this rich land and refined legacy to extract something new. With this act of producing comes obligation.

We cannot regress back to the colonial Western settler mindset of individualism. Indigenous values inform our future and our obligations to the land, to water, to trees—to our way in the world. Canadian design must embrace this moral obligation. We must function as a collective: At once Indigenous and settler, immigrant and refugee, we must be united through our shared past and present and future.

Together, we inhabit and must care for this land.

HEAVY ABUNDANCE is a viable future. The perpetual need to grow and innovate must remain, but in response to environmental degradation and social injustice. Canadian design can reframe our legacy of shameless ambition and disregard, and effectively evidence change. We are abundant, and so Canadian design must reconceptualize, redistribute, rearrange, and redesign in response. This is our duty, to redefine our aspirations, our processes, our way in the world—to provide a more hopeful and inclusive future.

Canada can do this now.

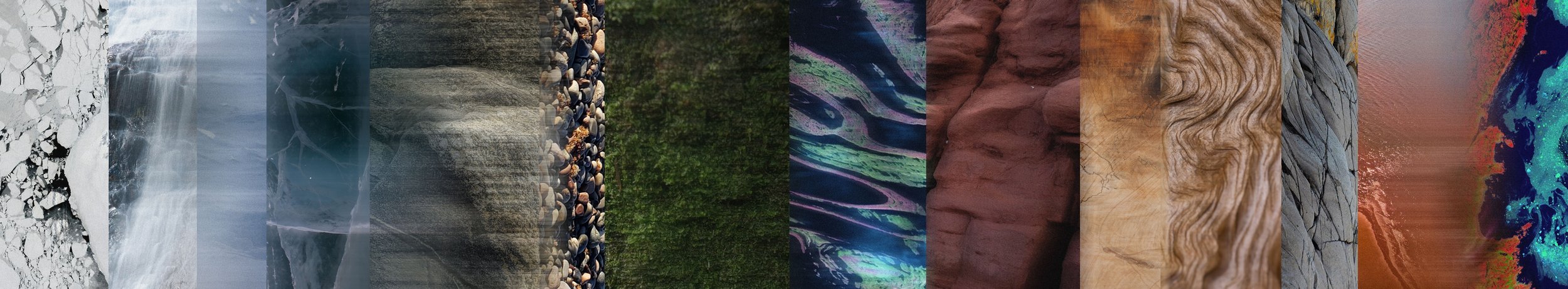

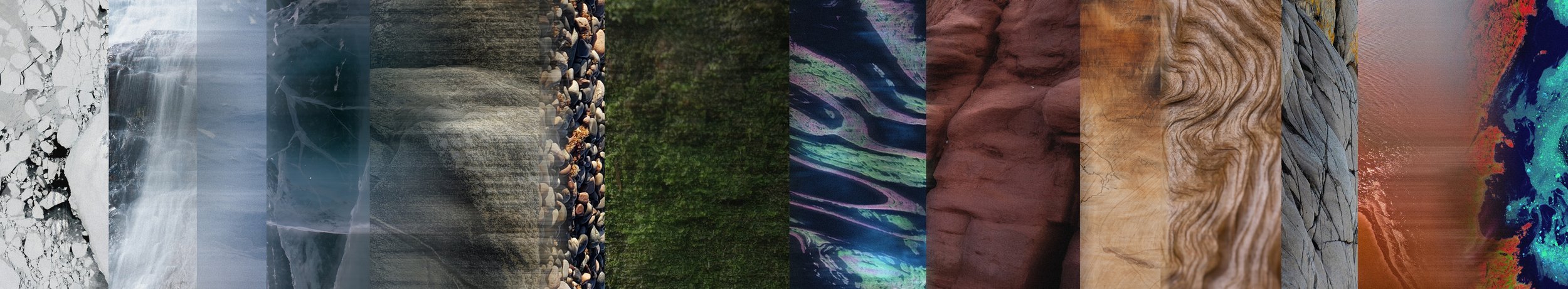

LAND

The land is our vessel and our water. It is the thread which unites it together. As our existence depends on the graciousness of our Earth, the importance of our immediate ecosystems heightens. Our duty to protect and conserve their complex and interlaced bionetworks becomes supreme. This is the equitable exchange that must dictate our actions.

Canadian identity relies on our land: on its magnitude, its scale and its diversity. The earth discloses the traditions and sacred rituals of our citizens and collectives, but it is also our strength. Despite the tensions between our regions, the land we share constructs a physical space which links antiquated notions of nationhood to a common Canadian identity. Our sacred land unites us in lieu of political force.

THE CONSTRUCTED IMAGE OF THE LANDSCAPE

Canada’s identity is fundamentally linked to its land, but more importantly to the constructed image of landscape. We see this context as both the vast, iconic, banal and relentless natural condition, as well as the shifting, spreading, common and iconic interventions we have used to manipulate these conditions.

LANDSCAPE becomes that on which we intervene, and the life and meaning of those interventions mature through time into our identity as they embed themselves. Landscape then becomes a hybrid construct composed of the memory of experience, its projected and sometimes contrived ‘scenic’ identity, as well as the shifted reality of the post-experience place. Canadian design must ‘reconstruct’ the landscape as fictive topographies, filmic and physical.

A RADICAL FUTURE FOR CANADIAN DESIGN

Canadian design must be radically polyglot. Architecture is a tool for translation, speaking multiple languages of diverse and distinct cultures to respond to a particularity of place. This dynamic exchange is visible through past and future generations of both Indigenous Peoples and immigration in what is now Canada. In this multicultural context, Canadian design must not be nationalistic or racial, but an equitable, inclusive, and sustainable lingua franca that adapts to and welcomes change.

Canadian design must be radically diasporic. From keepers of Turtle Island to European settlers and present-day immigration, Canadian architecture is an expression of place-making: incorporating the expression of one’s forsaken home to appropriate a space inclusive to all which occupy it. Hence, Canadian design must embody a spectrum of both space and time, advocating for past, present and future generations wherever they may be or come from. Canadian architecture must be home to all.

Canadian design must be radically inclusive. The public is bigger than the individual. In response, Canada must listen and seek out compromise. Its architecture should create, repair and revive relationships between communities, disciplines, objects, lands, waters, and space. In being social, it must come from a place of connectivity, of joy, and play. Collaborative and cross-disciplinary, its creatives spur designs better equipped to face practice and spatial challenges—an end to siloed thinking.

Design is the practice of decision making—in many cases on behalf of billions of people and with implications for other forms of life. To create in Canada requires both moral and design excellence. In the current storm of social and ecological emergencies, the need to cultivate new ways of thinking is pressing. It is imperative however that these actions remain universal and timeless through our values of responsibility, humility, plurality, and solidarity.

However bright the future may look, it is still menaced by an underserved and unrepresented community which is persistently ignored by singular colonialized disciplines and stakeholder groups. The key knowledge which historically divides the voices of those directly impacted by the outcomes of design processes and those tasked with designing solutions continues to stain our land. For Canada to be viable, its design must become circular, working through design challenges for more equitable, inclusive and sustainable futures.

Canadian design must be radically resilient

Climate change encapsulates new opportunities and challenges. Designers must reimagine cities with nature-based solutions to protect, create, and improve the urban. Only then will we be able to enhance cities’ abilities to adapt and mitigate eventual damages to our communities. Strengthening our understanding of circular designs, reuse, repurposing and upcycling strategies in architecture—and not expanding into unused and untouched areas—will propel us to a better, resilient and regenerative future.

Good design examines the relationships we create between one another, but also between people and their environments or objects, as we intervene in the world. The potential for Canadian design is rich. By celebrating biomimicry, preserving biodiversity, and incorporating natural and Indigenous processes, we can create a rich and complex vocabulary for design in Canada whilst also centering and honoring Indigenous people. This centering creates small-scale solutions that emphasize consideration over standardized and utilitarian approaches, hold tangible meaning and perform in synchronicity with technology.

Biodiversity and technology have co-evolved: Embedded in our land is a database of knowledge, information, and culture. It is how we use these systems that we will define our ability to adapt and care for our ecosystems throughout the ongoing challenge of post-covid environments, ongoing climate threats, global economic forces, oceanic waste, shifts in industry and labour, and evolving social and cultural paradigms.

Canadian design’s critical infrastructures can find protection in nature-based solutions and leave the Anthropocene behind to build a new stratigraphy which works within natural systems, providing honest well-being for cities and local communities.

Canadian design must be radically of the land. At its best, place-based architecture succeeds to respond to the topography, history and community that surrounds it. On a regional scale, it is an architecture of harmony in its ability to synthesize and adapt to surroundings. Canadian design must strive for these same principles: Diverse in its variety of geographical expanse and its puzzles of combined contexts, the Canadian land is a network of knowledge systems integrated within the ecosystem of Indigenous territories.

Canadian design must point towards a radical future. Its identity has been historically gridlocked in a state of unfolding, waiting for a clear and distinct outline the future to come. The time for action has arrived. No longer must we remain stagnant, modest, ‘nice’. The moment for us to rise as drivers of design has crystallized.

Canadian design must lead radically. Guided by goals of circular design processes and universal inclusivity, Canada can act as a central hub of innovation: Designers, researchers, and architects from across the land must speak out, grab reins, challenge one another, and put aside the characteristic humility of the Canadian ethos. Canadian design leadership must proclaim and declare, celebrate, and provoke not only itself but the world at large.

Canada can be equipped with the tools to create brighter futures where architectural projects become propositions for dreams of a better society, translating buildings to cities as new spatial artifacts oriented towards a present which benefits tomorrow. We must embrace and share our abundance.

Canadian design must embrace radical intricacies and eschew reductive thinking. There is a clear aesthetic and identity, and it is one of complexity, of many voices and shades of grey in both harmony and imbroglio. To create Canadian is to consider many diverse and nuanced voices to promote a shared inclusive identity, aesthetic and sense of belonging. It is a design of contradictions, with a vocabulary known for being both pragmatic and perplexing.

Canadian design is a radical manifesto for all. Canadian design finds its strengths in inclusionary practice and reverence for that which is already present. Its definition and purpose are more amorphous than concrete, and it must continuously question who is in its room while actively inviting in new participants and audiences.

In doing so, we can create a positive reactionism. We are interdependent: Issues of climate, resources and inequity are of global concern, and the practice of architecture has immense impacts on these. As designers, leading with kinship, we can begin to repair the systems ingrained within the built environment of our local and global communities.